|

Jimmie

Rodgers |

|

September 8, 1897 - May 26, 1933

Father of Country Music

Singing Brakeman

Mississippi Blue Yodeler

For those of you who may not be familiar with the music of Jimmie

Rodgers, a good place to start would be to click on the links and

listen to Jimmie's unique and original style.

Jimmie's first big hit: T For Texas (Blue Yodel No. 1 - November 30, 1927) - 184

Jimmie with full ochestration including brass: Waiting For A Train (October 22, 1928)

Jimmie's biggest selling composition by many artists over the years: Mule Skinner Blues (Blue Yodel No. 8 - July 11, 1930)

James Charles Rodgers, Jimmie, the man who started it all. Born in Meridian, Mississippi to

Jimmie Rodgers was born on September 8, 1897 in Meridian, Mississippi,

the youngest of three sons. His mother Eliza died in 1903 when he was a very young

boy, and Rodgers spent the next few years living with various relatives

in southeast Mississippi and southwest Alabama. He eventually returned

home to live with his father, Aaron Rodgers, a Maintenance of Way

Foreman on the Mobile and Ohio Railroad, who had settled with a new

wife in Meridian.

Jimmie's affinity for entertaining came at an early age, and the lure

of the road was irresistible to him. By age 13, he had twice organized

and begun traveling shows, only to be brought home by his father. Both

of these incidents shed light on his drive to perform. The first time

he was caught, he had stolen some of his sister-in-law's bedsheets and

joined them to make a crude tent. Upon his return to Meridian, he paid

for the sheets, having made enough money with his show! For the second

trip with his troupe, he had charged to his father (without his

knowing) an expensive sidewall canvas tent. It's not known whether or

not Jimmie paid for the tent, but not long after that, Mr. Rodgers

found Jimmie his first job working on the railroad, as waterboy on his

father's gang. A few years later, he became brakeman on the New Orleans

and Northeastern Railroad, a position secured by his oldest brother,

Walter, a conductor on the line running between Meridian and New

Orleans.

In 1924, at the age of 27, Jimmie contracted tuberculosis, and the

paradox of this development is bittersweet. The disease temporarily

ended his railroad career, but, at the same time, gave him the chance

to get back to his first love, entertainment. He organized a traveling

road show and performed across the southeast until, once again, he was

forced home after a cyclone destroyed his tent. He returned to railroad

work as a brakeman on the east coast of Florida at Miami, but

eventually his illness cost him his job. In vain, he relocated to

Tucson, Arizona (thinking the dry climate might have an effect on his

TB), and was employed as a switchman by the South Pacific; the job

lasted less than a year, and the Rodgers family (which by then included

wife Carrie and daughter Anita) settled back in Meridian in 1927.

It's not exactly known why Jimmie decided to travel to Asheville, North

Carolina, later that year. Some say he was searching for a rumored job

on the railroad (one that didn't exist), while others speculate that it

was the mountain air. Though he probably gave these as reasons, most

likely, it was due to the burgeoning music scene in North Carolina.

In February of 1927, Asheville's first radio station, WWNC, went on the

air, and on April 18, at 9:30 p.m., Jimmie and Otis Kuykendall

performed for the first time on the station. A few months later, Jimmie

recruited a group from Tennessee called the Tenneva Ramblers and

secured a weekly slot on the station as the Jimmie Rodgers

Entertainers. The performances provoked two separate comments that

hinted at Rodgers' future success. A review in The Asheville Times

remarked that "Jimmy (sic) Rodgers and his entertainers managed...with

a type of music quite different than [the station's usual material],

but a kind that finds a cordial reception from a large audience." And

from another columnist: "whoever that fellow is, he either is a winner

or he is going to be."

The Tenneva Ramblers originally hailed from Bristol, Tennessee, and in

late July of 1927, Rodgers' band mates got word that Ralph Peer, a

representative of Victor Talking Machine Company, was coming to Bristol

to audition and record area musicians. Rodgers and the group quickly

mobilized and arrived in Bristol on August 3. Later that same day, they

auditioned for Peer in an empty warehouse where he had set up the

company's recording equipment. Peer agreed to record them the next day.

That night, as the band discussed how they would be billed on the

record, an argument ensued, which led Jimmie to declare, "All

right...I'll just sing one myself."

Jimmie was on his own, another twist in a long list of fateful circumstances that changed musical history.

On Wednesday, August 4, Jimmie Rodgers completed his first session for

Victor. It lasted from 2:00 p.m. to 4:20 p.m. and yielded two songs:

"Sleep, Baby, Sleep" and "The Soldier's Sweetheart." For the test

recordings, Rodgers received $100.

The recordings were released on October 7, 1927, to modest success, and

in November of that year, Jimmie, determined more than ever to make it

in entertainment, headed to New York City with two goals: to find out

the exact sales status of the first recordings, and to try to arrange

another session with Peer.

Peer agreed to record him again, and the two met in Philadelphia before traveling to Camden, New Jersey, to the Victor studios.

Four songs made it out of this session. "Ben Dewberry's Final Run";

"Mother Was A Lady"; "Away Out on the Mountain"; and "T for Texas." In

the next two years, the acetate that contained "T for Texas" (released

as "Blue Yodel") and "Away Out on the Mountain" sold nearly half a

million copies, which was impressive enough to rocket Rodgers into

stardom. After this, he got to determine when Peer and Victor would

record him, and he sold out shows whenever and wherever he played.

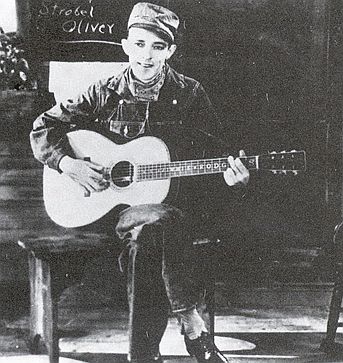

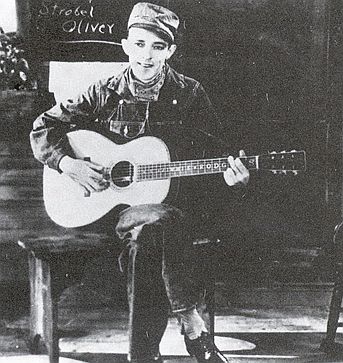

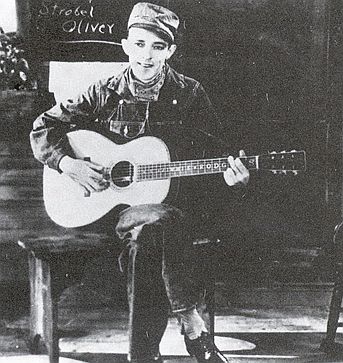

In the next few years, Rodgers was very busy. He did a movie short, The

Singing Brakeman, and made various recordings across the country. He

toured with humorist Will Rogers as part of a Red Cross tour across the

Midwest. On July 16, 1930, he even recorded "Blue Yodel #9" (also known

as "Standin' on the Corner") with a young jazz trumpeter named Louis

Armstrong, whose wife, Lillian, played piano on the track.

Rodgers' next to last recordings were made in August of 1932 in Camden

and it was clear that TB was getting the better of him. He had given up

touring by that time but did have a weekly radio show in San Antonio,

Texas, where he'd relocated when "T for Texas" became a hit.

With the country in full grip of the depression, the practice of making

field recordings was quickly fading, so in May of 1933, Rodgers

traveled again to New York City for a group of sessions beginning May

17. He started these sessions recording alone and completed four songs

on the first take. But there was no question that Rodgers was running

out of track. When he returned to the studio after a day's rest, he had

to record sitting down and soon retreated to his hotel in hopes of

regaining enough energy to finish the songs he'd been rehearsing.

The recording engineer hired two session musicians to help Rodgers when

he came back to the studio a few days later. Together, they recorded a

few songs, including "Mississippi Delta Blues." For his last song of

the session, however, Jimmie chose to perform alone, and as a matching

bookend to his career, recorded "Years Ago" by himself, finishing as

he'd started years earlier, just a man and his instrument. Within 36

hours, "The Father of Country Music" was dead.

Thankfully, his legend and legacy are alive and well. - http://www.jimmierodgers.com/

His brass plaque in the Country

Music Hall of Fame reads, "Jimmie Rodgers' name stands foremost in the

country music field as the man who started it all." This is a fair

assessment. The "Singing Brakeman" and the "Mississippi Blue Yodeler,"

whose six-year career was cut short by tuberculosis, became the first

nationally known star of country music and the direct influence of many

later performers from Hank Snow and Ernest Tubb and Hank Williams to

Lefty Frizzell and Merle Haggard. Rodgers sang about rounders and

gamblers, bounders and ramblers -- and he knew what he sang about. At

age 14 he went to work as a railroad brakeman, and on the rails he

stayed until a pulmonary hemorrhage sidetracked him to the medicine

show circuit in 1925. The years with the trains harmed his health but

helped his music. In an era when Rodgers' contemporaries were singing

only mountain and mountain/folk music, he fused hillbilly country,

gospel, jazz, blues, pop, cowboy, and folk; and many of his best songs

were his compositions, including "TB Blues," "Waiting for a Train,"

"Travelin' Blues," "Train Whistle Blues," and his thirteen blue yodels.

Although Rodgers wasn't the first to yodel on records, his style was

distinct from all the others. His yodel wasn't merely sugar-coating on

the song, it was as important as the lyric, mournful and plaintive or

happy and carefree, depending on a song's emotional content. His

instrumental accompaniment consisted sometimes of his guitar only,

while at other times a full jazz band (horns and all) backed him up.

Country fans could have asked for no better hero/star -- someone who

thought what they thought, felt what they felt, and sang about the

common person honestly and beautifully. In his last recording session,

Rodgers was so racked and ravaged by tuberculosis that a cot had to be

set up in the studio, so he could rest before attempting that one song

more. No wonder Jimmie Rodgers is to this day loved by country music

fans.

The youngest son of a railroad man, Jimmie Rodgers was Born September

8, 1897 in Geiger, Alabama. Following his mother's death in 1904, he

and his older brother went to live with their mother's sister, where he

first became interested in music. Jimmie's aunt was a former teacher

who held degrees in music and English, and she exposed him to a number

of different styles of music, including vaudeville, pop and dance hall.

Though he was attracted to music, he was a mischievous boy and often

got into trouble. When he returned to his father's care in 1911, Jimmie

ran wild, hanging out in pool halls and dives, yet he never got into

any serious trouble. When he was 12, he experienced his first taste of

fame when he sang "Steamboat Bill" at a local talent contest. Rodgers

won the concert and, inspired by his success, he decided to head out on

the road in his own traveling tent show. His father immediately tracked

him down and brought him back home, yet he ran away again, this time

joining a medicine show. The romance of performing with the show wore

off by the time his father hunted him down. Given the choice of school

or the railroad, Jimmie chose to join his father on the tracks.

For the next ten years, Rodgers worked on the railroad, performing a

variety of jobs along the south and west coasts. In May of 1917, he

married Sandra Kelly after knowing her for only a handful of weeks; by

the fall, they had separated, even though she was pregnant (their

daughter died in 1938). Two years later they officially divorced, and

around the same time, he met Carrie Williamson, a preacher's daughter.

Rodgers married Carrie in April of 1920, while she was still in high

school. Shortly after their marriage, Jimmie was laid off by the New

Orleans & Northeastern Railroad, and he began performing various

bluecollar jobs, looking for opportunities to sing. Over the next three

years, the couple was plagued with problems, ranging from financial to

health -- the second of their two daughters died of diphtheria six

months after her birth in 1923. By that time, Rodgers had begun to

regularly play in traveling shows, and he was on the road at the time

of her death. Though these years were difficult, they were important in

the development of Jimmie's musical style as he began to develop his

distinctive blue yodel and worked on his guitar skills.

In 1924, Jimmie Rodgers was diagnosed with tuberculosis, but instead of

heeding the doctor's warning about the seriousness of the disease, he

discharged himself from the hospital to form a trio with fiddler Slim

Rozell and his sister-in-law Elsie McWilliams. Rodgers continued to

work on the railroad and perform black face comedy with medicine shows

while he sang. Two years after being diagnosed with TB, he moved his

family out to Tucson, Arizona, believing the change in location would

improve his health. In Tucson, he continued to sing at local clubs and

events. The railroad believed these extracurricular activities

interfered with his work and fired him. Moving back to Meridian, Jimmie

and Carrie lived with her parents, before he moved away to Asheville,

North Carolina in 1927. Rodgers was going to work on the railroad, but

his health was so poor he couldn't handle the labor; he would never

work the rails again. Instead, he began working as a janitor and a cab

driver, singing on a local radio station and events as well. Soon, he

moved to Johnson City, Tennessee, where he began singing with the

string band the Tenneva Ramblers. Prior to Rodgers, the group had

existed as a trio, but he persuaded the members to become his backing

band because he had a regular show in Asheville. The Ramblers relented

and the group's name took second billing to Rodgers, and the group

began playing various concerts in addition to the radio show.

Eventually, Rodgers heard that Ralph Peer, an RCA talent scout, was

recording hillbilly and string bands in Bristol, Tennessee. Jimmie

convinced the band to travel to Bristol, but on the eve of the

audition, they had a huge argument about the proper way they should be

billed, resulting in the Tenneva Ramblers breaking away from Rodgers.

Jimmie went to the audition as a solo artist and Peer recorded two

songs -- the old standards "The Soldier's Sweetheart" and "Sleep, Baby,

Sleep" -- after rejecting Rodgers' signature song, "T for Texas."

Released in October of 1927, the record was not a hit, but Victor did

agree to record Rodgers again, this time as a solo artist. In November

of 1927, he cut four songs, including "T for Texas." Retitled "Blue

Yodel" upon its release, the song became a huge hit and one of only a

handful of early country records to sell a million copies. Shortly

after its release, Jimmie and Carrie moved to Washington, where he

began appearing on a weekly local radio show billed as the Singing

Brakeman. Though "Blue Yodel" was success, its sales grew steadily

throughout early 1928, which meant that the couple weren't able to reap

the financial benefits until the end of the year. By that time, Jimmie

had recorded several more singles, including the hits "Way Out on the

Mountain," "Blue Yodel No. 4," "Waiting for a Train" and "In the

Jailhouse Now." On various sessions, Peer experimented with Rodgers'

backing band, occasionally recording him with two other string

instrumentalists and recording his solo as well. Over the next two

years, Peer and Rodgers tried out a number of different backing bands,

including a jazz group featuring Louis Armstrong, orchestras, and a

Hawaiian combo.

By 1929, Jimmie Rodgers had become an official star, as his concerts

became major attractions and his records consistently sold well. During

1929, he made a small film called The Singing Brakeman, recorded many

songs, and toured throughout the country. Though his activity kept his

star shining and the money rolling in, his health began to decline

under all the stress. Nevertheless, he continued to plow forward,

recording numerous songs and building a large home in Kerrville, Texas,

as well as working with Will Rogers on several fund-raising tour for

the Red Cross that were designed to help those suffering from the

Depression. By the middle of 1931, the Depression was beginning to

affect Rodgers as well, as his concert bookings decreased dramatically

and his records stopped selling. Despite the financial hardships,

Jimmie continued to record.

Not only did the Great Depression cut into Jimmie's career, but so did

his poor health. He had to decrease the number of concerts he performed

in both 1931 and 1932, and by 1933, his health affected his recording

and forced him to cancel plans for several films. Despite his

condition, he refused to stop performing, telling his wife that "I want

to die with my shoes on." By early 1933, the family was running short

on money, and he had to perform anywhere he could -- including

vaudeville shows and nickelodeons -- to make ends meet. For a while he

performed on a radio show in San Antonio, but in February he collapsed

and was sent to the hospital. Realizing that he was close to death, he

convinced Peer to schedule a recording session in May. Rodgers used

that session to provide needed financial support for his family. At

that session, Jimmie was accompanied by a nurse and rested on a cot in

between songs. Two days after the sessions were completed, he died of a

lung hemorrhage on May 26, 1933. Following his death, his body was

taken to Meridian by train, riding in a converted baggage car. Hundreds

of country fans awaited the body's arrival in Meridian, and the train

blew its whistle consistently throughout its journey. For several days

after the body arrived in Rodgers' hometown, it lay in state as

hundreds, if not thousands, of people paid tribute to the departed

musician.

The massive display of affection at Jimmie Rodgers' funeral services

indicated what a popular and beloved star he was during his time. His

influence wasn't limited to the '30s, however. Throughout country

music's history, echoes of Jimmie Rodgers can be heard, from Hank

Williams to Merle Haggard. In 1961, Rodgers became the first artist

inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame; 25 years later, he was

inducted as a founding father at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

Though both honors are impressive, they only give a small indication of

what Rodgers accomplished -- and how he affected the history of country

music by making it viable, commercially popular medium -- during his

lifetime. -- David Vinopal - http://www.alamhof.org/rodgersj.htm

Jimmie Rodgers's Story

James Charles Rodgers, known professionally as the Singing Brakeman and

America’s Blue Yodeler, was the first performer inducted into the

Country Music Hall of Fame. He was honored as the Father of Country

Music, “the man who started it all.” From many diverse

elements—the traditional melodies and folk music of his southern

upbringing, early jazz, stage show yodeling, the work chants of

railroad section crews and, most importantly, African-American

blues—Rodgers evolved a lasting musical style which made him

immensely popular in his own time and a major influence on generations

of country artists. Gene Autry, Ernest Tubb, Hank Snow, Lefty Frizzell,

Bill Monroe, Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, Tanya Tucker, and Dolly Parton

are only a few of the dozens of stars who have acknowledged the impact

of Jimmie Rodgers’s music on their careers.

Rodgers was the son of a railroad section foreman but was attracted to

show business. At thirteen he won an amateur talent contest and ran

away with a traveling medicine show. Stranded far from home, he was

retrieved by his father and put to work on the railroad. For a dozen

years or so, through World War I and into the 1920s, he rambled far and

wide on “the high iron,” working as call boy, flagman,

baggage master, and brakeman, all the while polishing his musical

skills and looking for a chance to earn his living as an entertainer.

After developing tuberculosis in 1924, Rodgers gave up railroading and

began to devote full attention to his music, organizing amateur bands,

touring with rag-tag tent shows, playing on street corners, taking any

opportunity he could find to perform. Success eluded him until the

summer of 1927. In Asheville, North Carolina, he wangled a regular (but

unpaid) spot on local radio station WWNC and persuaded the Tenneva

Ramblers, a stringband from Bristol, Tennessee-Virginia, to join him as

the Jimmie Rodgers Entertainers. When the radio program was abruptly

canceled, they found work at a resort in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

There they learned that Ralph Peer, an agent for the Victor Talking

Machine Company, was making field recordings in Bristol, not far away.

Rodgers quickly loaded up the band, went to Bristol, and succeeded in

gaining an audition with Peer. Before they could record, however, the

group quarreled over billing and broke up. Deserted by the band,

Rodgers persuaded Peer to let him record alone, accompanied only by his

own guitar.

Prompted by the public’s unusually strong response to

Rodgers’s first release (“Sleep, Baby, Sleep,” paired

with “The Soldier’s Sweetheart”), Peer arranged for

Rodgers to record again in November at Victor’s home studios in

Camden, New Jersey. From this session came the immortal “Blue

Yodel (T for Texas),” Rodgers’s first big hit. Within

months he was on his way to national stardom, playing first-run

theaters, broadcasting regularly from Washington, D.C., and signing for

a vaudeville tour of major Southern cities on the prestigious Loew

Circuit.

In the ensuing five years he traveled to Victor’s studios in

numerous cities across the nation, including New York and Hollywood,

eventually recording 110 titles, including such classics as

“Waiting for a Train,” “Daddy and Home,”

“In the Jailhouse Now,” “Frankie and Johnny,”

“Treasures Untold,” “My Old Pal,” “T. B.

Blues,” “My Little Lady,” “The One Rose,”

“My Blue-Eyed Jane,” “Miss the Mississippi and

You,” and the series of twelve sequels to “Blue

Yodel” for which he was most famous. In 1929 Rodgers appeared in

a movie, The Singing Brakeman, a fifteen-minute short made in Camden by

Columbia. Best known for his solo appearances on stage and record, he

also worked with many other established performers of the time, touring

in 1931 with Will Rogers (who jokingly referred to him as “my

distant son”) and recording with such country music greats as the

Carter Family, Clayton McMichen, and Bill Boyd, and in at least one

instance with a jazz star of major national prominence, Louis

Armstrong, who appears with him on “Blue Yodel No. 9.” One

of the first white stars to work with black musicians, Rodgers also

recorded with the fine St. Louis bluesman Clifford Gibson.

Rodgers’s career reached its high point during the years 1928 to

1932. By late 1932 the Depression was taking its toll on record sales

and theater attendance, and Rodgers’s failing health made it

impossible for him to pursue the movie projects and international tours

he had planned. Through the spring of 1933 he tried, with little

success, to book personal appearances. In May he went to New York to

fulfill his contract with RCA Victor for twelve more recordings. It

took him a week to finish these sessions, resting between takes. Two

days later, on May 26, he collapsed on the street and died a few hours

later of a massive hemorrhage in his room at the Hotel Taft.

Jimmie Rodgers’s impact on country music can scarcely be

exaggerated. At a time when emerging “hillbilly music”

consisted largely of old-time instrumentals and lugubrious vocalists

who sounded much alike, Rodgers brought to the scene a distinctive,

colorful personality and a rousing vocal style which in effect created

and defined the role of the singing star in country music. His records

turned the public’s attention away from rustic fiddles and

mournful disaster songs to popularize the free-swinging, born-to-lose

blues tradition of cheatin’ hearts and faded love, whiskey rivers

and stoic endurance. Although Rodgers constantly scrabbled for material

throughout his career, his recorded repertoire was remarkably broad and

diverse, ranging from love songs and risque´ ditties to whimsical

blues tunes and even gospel hymns. There were songs about railroaders

and cowboys, cops and robbers, Daddy and Mother, and

home—plaintive ballads with all the nostalgic flavor of

traditional music but invigorated by a distinctly original approach and

punctuated by Rodgers’s yodel and unorthodox runs, which became

his trademarks. - Nolan Porterfield - http://www.countrymusichalloffame.com/site/inductees.aspx?cid=162#

Died at the Taft Hotel, NY, NY - T for Texas - Blue Yodel No. 1 - Sold over 1 Million copies